|

Two days ago, I completed a 12-day, approximately 240-mile (386 km) self-supported hike and float (packrafted about the last 40 miles) sea-to-sea across Iceland from the south coast to a fjord on the north coast. Most of the route was on trails, some on dirt roads, some on river, while a couple of sections were cross country in trailless wilderness (among the highlights). It was mostly amazing, at times challenging, and very uncertain as I had little to no information about most of the route. Iceland has been crossed many times but never by this route as far as I can tell.

My intention was to do a cool trip that tied in with my research work here in Iceland centered in part on conflicts between energy development and conservation as well as issues around roads and wilderness, and similar intersecting topics. This allowed me to gain a lot of first hand familiarity with my main research subject and to learn the land one step or stroke at a time, which is incomparably more intimate than any other form of travel. I intend to integrate my experiences and ample photos from this trip into a published article based on my research. I hope to find an outlet willing to run my article. Stay tuned (it will take many months at least). I also plan to create a great presentation about it that I hope to give at various venues. PS: DISCLAIMER - some sections of this route are extremely dangerous; do not attempt to repeat. Website here.

0 Comments

"In the wilderness, you have left cyberspace behind in one sense, but not in another. You’re still surrounded by it physically, and it continues to offer itself as a possibility of information and communication. Isn’t it Luddite to refuse the offer altogether? Doesn’t a refusal betray a timid failure to come to terms with technology? And aren’t you drawing an arbitrary line through technology? After all, everything you wear and carry is high tech, the fabrics of your clothing and shoes, the poles of your tent, the cooking utensils, the binoculars, the watch, and the map. There are not only questions of consistency but also questions of ethics. You can get lost or injured in the wilderness. If lost, is it responsible to make the Search and Rescue people pay in toil and time for your precious refusal to carry a GPS device not to mention the anxiety you are causing your beloved when you’re not showing up at the appointed time? Similarly, when someone in your party is injured and immobilized, is it right to jeopardize the person’s health or even life while you’re getting help? Shouldn’t you have some electronic device that would have summoned help quickly and effectively? Information technology might also make your hike more deeply informed and moving. Say you carry a device with a camera; you point it at a particular peak, and an app informs you that this is Chief Mountain where, as James Welch tells us at the beginning of Fools Crow, ‘Eagle Head and Iron Breast had dreamed their visions in the long-ago.’ Is such a device much different from a knowledgeable companion and in fact more reliable and better informed than a human could be (though of course incapable of a conversation)? If such a snapshot makes your trip more valuable, why not ‘one day’ not far in the future wear a pair of spectacles from Google’s Project Glass? It won’t be very different or more obtrusive than the sunglasses you’re wearing now. It responds to voice commands and on request projects fourteen icons on your visual field. If you worry about an impending snowstorm that may blind you on your ascent to Stuart Peak, you can call up the weather forecast. If your worry was unfounded and you made the peak, but took a wrong turn on your descent, you call up a map, and it shows you before your very eyes and in vivid detail where to go to reach your campsite. If you suddenly remember a crucial appointment you should have scheduled, you summon your calendar and record a reminder. If on your way down you come upon a lovely flower, unknown to you, you hold it in your gaze and are told: It’s the Mountain Bog Gentian, and here are its interesting facts. As you approach your camp, there is a high-country sunset of ravishing beauty, just the thing to impress and provoke envy in your colleagues. You take a picture and send it to them. But why not send them a continuous video of your entire hike, fine-grained and in three dimensions, complete with audio? In fact on their giant plasma screen with perfect stereo sound, they can share your entire experience, a better experience in fact since they won’t have to suffer your chills and exhaustion and can fast-forward through all the tedious part of hiking and camping. Come to think of it, why not just stay home and rent the perfect wilderness hike video? If exhaustion has to be part of the experience, you can watch it while doing stairs on your stair climber machine. I have traced a trajectory from the reasonable via the plausible to the laughable. It shows us how seemingly inescapable, continuous, and seductive the culture of technology is. You enter the wilderness with reasonable moral concerns, follow the logic of technology, and end up in the gym, watching a screen. It seems that any line you may draw across the trajectory is arbitrary, including the legal line between wilderness and non-wilderness." 1 “Technology as a way of taking up with reality has put the power of technological information in the service of radical disburdenment. At the limit, virtual reality takes up with the contingency of the world by avoiding it altogether. The computer, when it harbors virtual reality, is no longer a machine that helps us cope with the world by making a beneficial difference in reality; it makes all the difference and liberates us from actual reality.” 2 1 Albert Borgmann in The Force of Wilderness Within the Ubiquity of Cyberspace (AI & Society, 2017) 2 Borgmann, Holding On to Reality: The Nature of Information at the Turn of the Millennium. p. 183. Images from•hiking.org/2015/09/27/the-gadget-hiker/

•https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/photo/android-red-dawn-royalty-free-image/1248714443 •https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PyFN_FYwqvc •https://www.reddit.com/media?url=https%3A%2F%2Fi.redd.it%2Fmpqu13erce611.jpg •https://payload374.cargocollective.com/1/16/527053/9780406/--illustrations-02-LevelUp-05_800.png •https://www.pinterest.com/pin/670121619531984065/ •https://i.ytimg.com/vi/s4SiDIi_gfc/maxresdefault.jpg  "The most serious form of environmental pollution is always mind pollution. Environmental reform most fundamentally depends on changing the way we think. Scientists may have answers to environmental problems, but the answers are not solutions unless they change behavior. Enough technology! It's time to listen to the humanists again." --Roderick Nash (2001) From: Noel, T. J., & Fielder, J. (2001). Colorado, 1870-2000, revisited: the history behind the images. Big Earth Publishing. Americans, the reelection of Joe Biden is absolutely vital. Climate change is a leading reason why. Even if you disagree with some of his actions and policies, e.g., Gaza or COVID response, or are concerned about his age, please don't sit this one out or throw your vote away on a third party (effectively giving a vote to Trump). Not now. Biden has done perhaps more than any other single person in combating climate change through the passing of the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Act. But there is still a lot more that needs to be done--urgently. If you think the southern border is a mess or you are appalled by gruesome wars, what we are seeing now is nothing compared to what climate change will continue to bring. November is still a long way off, but please keep this in mind. Or better yet, start working now to keep him in office. (Congress matters too).

From my dissertation:

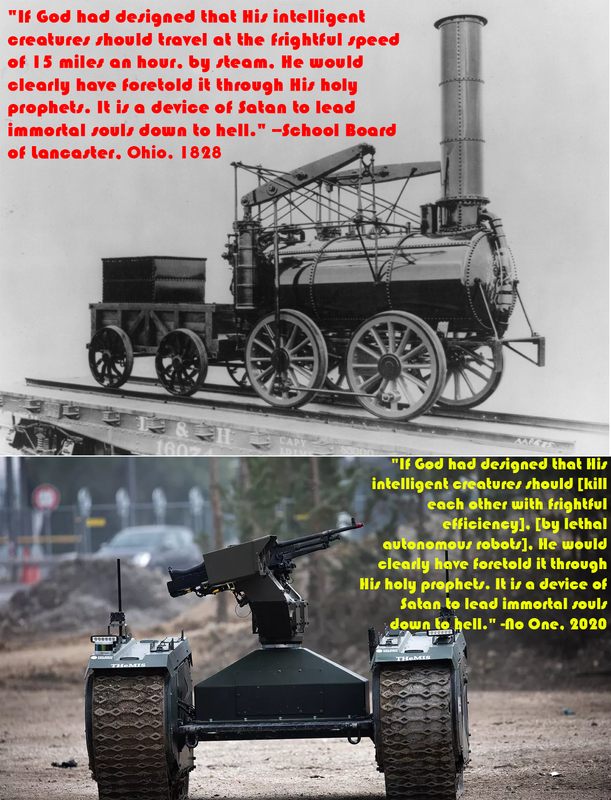

Keeping, tending, or managing the wild is a paradox. Nature loses something of its wildness once brought under the wing of human concern. Although human impacts on nature are often thought to also curb nature’s wildness, not all impacts are the same. Some, like climate change, biodiversity loss, invasive species, and certain forms of pollution are globally pervasive and have been, up until now, inadvertent. For climate change in particular, the present challenge is to shift from inadvertent impact to deliberate design of the global climate. This is no small feat, requiring complex, international negotiations that involve every sector of the economy with millions of human lives and the existence of nations at stake. Nor is it a small change in our relationship with the planet. Humanity has inadvertently become a global, geological force. Now we must become deliberate designers of the climate. As our technological power increases, so do our impacts, as does the necessity and possibility of design. As we liberate the planet from environmental degradation and pollutants, however, a new risk emerges—that the global climate and other aspects of our world become technological artifacts. As I mentioned in Chapter 2, science, while integral to shaping a sustainable, livable future, is also implicated in technocratic management—as is modern ethics. Without something akin to the impulse in John Muir or the cultural traditions of the Tlingit—if we slip into conceiving and treating the earth as merely an engineering problem or purveyor of services—we risk living on a sanitized earth—a dystopia of total technical design. #technocracy #technocratic In an undisclosed location somewhere near the triple border of Nebraska, Colorado, and Wyoming, is something truly extraordinary: protrusions—things sticking up out of the land into the sky. You even have to tilt your head up a little bit to take a gander. That’s really something after a gabillion miles of flat stuff. In an even more undisclosed location near that is a gorgeous, windswept blue pond—ringed on one side by a row of ancient automobiles circa 1950s perhaps—embankments placed nose to tail in an unceasing prairie traffic jam. Rusting, rotting, shattered glass—a stubborn line of Detroit’s finest in spackled dull red holding the landscape together between glistening marine hues and emerald green spring grasses stretching as least as far as the Medicine Bow. Sometimes you have to go east to go west, and there’s always the chance that heading west from here is really only a circling back around again. It turns out—contrary to common misunderstandings—that medieval Europeans kept themselves quite clean. Not only that, but they utilized industrial waste heat, a practice that—in the digital age—we seem to only just now be rediscovering.

“Ordinary people in medieval cities bathed regularly in public bathhouses. These were often built close to bakeries, to share heat produced by the ovens.” Source. This basic waste heat reuse model has been (unknowingly) replicated at Iceland's Blue Lagoon, for instance. Read more about utilizing heat waste here. This is just one of many archaic innovations that may help us to live more sustainably. Another inspiring one is bâdgir or wind-catchers from Ancient Persia (along with “an underground refrigeration structure called yakhchāl, an underground irrigation system called qanats”). Learn more about this here. This is a very interesting finding by another Dr. Dunn and her colleague. It sheds critical light on a longstanding debate about to what extent ancient human presence in North America was benign. A major talking point of constructivist, anti-wilderness thinkers is that large-scale human-induced fire has long been a part of North American landscapes and so "wilderness" (they like to scare quote it) is an unjust myth. There is a grain of truth to this and it is undeniable that the indigenous people of North America (and elsewhere) have been subjected to many injustices. Nevertheless, the basic anti-wilderness position and argument, which includes those relying on human-induced fires is quite wrong. First, because for countless millions of years prior to the quite recent (geologically and evolutionarily speaking) arrival of humans on this continent, wilderness was the basic condition here in a Pleistocene bonanza of large megafauna. And second, as this study reveals, because humans were likely integral to the widespread extinction of many species and thus, while it IS the case that human-induced fire was widespread (though by no means ubiquitous - another fallacy in the constructivist argument) for a decent length of time (let's say 14,000 years more or less), it was destructive in many ways. Thus it does not follow that it is a good thing and SHOULD have been a part of this landscape. Regardless, it is a necessary work in progress to do right by the indigenous people of this continent even if their ancestors are implicated in ecological destruction (as no human society is likely immune from). And it is also the case that since these early extinctions, the cultural development of North American indigenous peoples, including land management practices, spiritual connections, and ethical systems, has become something admirable in many ways due to learning from past mistakes, so this revelation doesn't take away from this. Just as we can appreciate the land management practices, spiritual connections, and ethical systems encapsulated in the ethical and practical innovation of wilderness in the contemporary context.

Fossil fuel companies (and their corrupt government operatives) aren't going to stop themselves - we have to force them. Here's an outlet to begin this world-historically important work: a Global Climate Strike is planned by Fridays for Future on September 15, and a March to End Fossil Fuels will be held in New York and around the world on September 17 (LINK HERE).

“Anything else you’re interested in is not going to happen if you can’t breathe the air and drink the water. Don’t sit this one out. Do something. You are by accident of fate alive at an absolutely critical moment in the history of the planet.” --Carl Sagan Is this finally the climate change equivalent of the dust bowl? Our "Black Sunday"? In 1935, after denial and inaction by D.C. legislators, a plume of dust from Oklahoma darkened the skies--landing directly on D.C.--finally making the issue inescapable.

I have a glimmer of hope, but also realize that a significant portion of our political landscape is hopelessly out of touch with reality (I'm talking to you, [most] Republicans and Joe Manchin) to the point of not only denying ample scientific evidence, but even their own senses. "[fire historian Stephen] Pyne sees a small glimmer of hope: Just like the day in 2020 when San Francisco turned orange, this dramatic smoke event might help show the urgency of fighting climate change. “These large smoke palls may have the same motivating effect as the Dust Bowl squalls in the '30s,” says Pyne. “That was a remote environmental issue in the middle of the country where hardly anybody lived. And now it's at the steps of the Capitol.”" (from here)  From: https://vimeo.com/239874194 From: https://vimeo.com/239874194 I rarely watch television, and if I do, I make a superhuman effort to avoid advertisements. I happened though to catch a few of the recent Stanley Cup games in a Denver restaurant in which I controlled neither the channel nor the volume, and one commercial for a Toyota 4Runner stood out to me. It featured said machine (shiny and new of course) blasting up roads in a natural setting, with a deep male voice narrating something or other, and generic guitar riffs in the background. It culminated with the 4Runner at a scenic view with the massive words “Keep it Wild” plastered across the screen overtop the vehicle and scenery. After some internet searching, I discovered that Toyota has been running this campaign for around 10 years, if not more. I have no specific beef with Toyota (well, besides their financing of Big Lie supporting politicians and mixed environmental record). I actually own a Toyota—a 2000 Tacoma to be exact—a real truck if there ever was one. It’s less than ideal in terms of gas mileage and for city driving (I try to drive it as little as possible, choosing to bike, bus, and carpool instead), but it delivers for camping and getting into the mountains. I suppose that is the point of the ad campaign. Nevertheless, Toyota’s slogan sits somewhere between irresponsible and insulting. If the wild is anything, it is beyond the limits of motorized access. To be clear, the wild is in a sense everywhere—the weeds in your driveway, the moon looming above a city skyline, the hummingbird flitting by your window—each are wild things that all of us experience every day. But the real stuff—intact landscapes where a variety of creatures, large and small (including predators), can live their lives more or less as they have for eons with minimal human interference and influence—and, once entered by humans on their own two legs or with paddle in hand or on horseback, know that this is a realm apart from their usual world—a place that commands respect in part because it is dangerous and is not theirs to command—a place that overwhelms sense and sensibility with an order apart. More practically speaking, wilderness means in part a specific form of land designation that legally bars road development and mechanized and motorized intrusion. The 1964 Wilderness Act was motivated largely by the threats that these created to the last remaining undeveloped federal lands—usually in the most rugged mountains or most remote deserts. I for one am bounteously grateful for the foresight of those over 50 years ago to leave some places protected as such—a respite from the noise, emissions, and consumptive ease of the everyday. Presently, around 2% of all the land in the “lower 48” is protected as wilderness. The rest is within striking distance of a road and otherwise converted for human uses. But even with a variety of protections in place against motorized incursion, it is often regarded by land management professionals as an ongoing threat to Wilderness and other public lands, though not among the largest threats to Wilderness. The late environmentalist and author Edward Abbey famously railed against “Industrial Tourism” in the National Parks in his best-known work, Desert Solitaire, arguing among other things that the experience is diminished by being confined to an automobile: “A man [or you know whoever] on foot, on horseback or on a bicycle will see more, feel more, enjoy more in one mile than the motorized tourists can in a hundred miles...Those who are familiar with both modes of travel know from experience that this is true; the rest have only to make the experiment to discover the same truth for themselves.” More important than the quality of the experience of nature is the pressing need to increase the size and interconnectedness of protected landscapes to stymie and reverse biodiversity loss. This will certainly entail decreasing road access in some areas. While slowing climate change (including its profound impacts on wild nature) requires decreasing fossil fuel consumption, which will necessitate—among many other things—slowing the production and dissemination of personal vehicles powered by the internal combustion engine. It is therefore more than a little Orwellian that an automobile company in an SUV ad should help itself to language to which it is totally unentitled. Toyota’s slogan undoubtedly sells 4Runners, but it certainly doesn’t “Keep it Wild.” #wild #wilderness #TOYOTA #keepitwild The Taj Mahal at the Meeting Place of Life and Death, Splendor and Horror, Nature and Culture7/7/2022 The Taj Mahal is a contradiction. It is easily one of the most superb human creations to ever grace our planet—gorgeous, immaculate, perfect—everything they say and more. It is an exquisitely proportioned aesthetic wonder—a national treasure, a world treasure, a living treasure. It is also a hulking monument to the dead—the tomb of an emperor’s favorite wife. And in a country that has long struggled with poverty, the Taj Mahal was built at great expense; and it is at great expense that it continues to be maintained for the benefit of the millions of tourists who visit it year-round. The most striking contradiction may however be that this new seventh wonder—the subject of the world’s adoration and fawning—sits next to one of the world’s most polluted rivers. The Yamuna River is so polluted in fact that it is considered dead—an open sewer of industrial and human filth. The main sources of pollution are untreated sewage, pesticide runoff, plastic litter, and waste from leather and jewelry manufacturing facilities. It has long been considered by experts in India to be unsavable (in contrast to more recent hopeful assessments). The contrast between the immaculateness of the Taj and the abysmal condition of the nearby river could not be more striking. And nested within this contradiction is another: the Yamuna is considered by Hindus to be one of the holiest rivers. So, to recap, we have a monument to the dead, adored by the living, on a dead river, revered by the living. It might seem that there is a moral here about human priorities gone awry: a charismatic human construction prioritized over an element of nature. Perhaps this is true, but there may be a deeper story in all of this. For the Taj Mahal is also succumbing to decay—some due to the inevitably of time—much however due to local pollutants, including airborne industrial contaminants. The most obvious symptom is surface discoloration, but crumbling of the façade, and possible structural concerns with the foundation are others. Maintaining the Taj is a painstaking and time-consuming process, incorporating, among other techniques, the use of mud baths. The longstanding prominent theory of acid rain from sulfur dioxide emissions as the main culprit of exterior degradation has however recently been supplanted in favor of hydrogen sulfide emitted from the highly toxic Yamuna River. It is also now thought that the Taj is gravely threatened by the decay of its foundations due to the dropping water levels of the Yamuna. The state of the Taj Mahal is therefore deeply entwined with that of the river and the surrounding air. The primary moral lesson then may be the deep intertwinement of the natural and the cultural—each dependent in many ways on the other. Our lives and those things we treasure most cannot persist without looking after the most fundamental aspects of our existence. The truth is that great effort has gone into working to preserve and restore both the Taj Mahal and the Yamuna River. A final lesson is thus that actualizing our ideals and working through complex problems is at times frustrating and heartbreaking and not always successful. I still hope against all odds that the Taj will continue to sit in magnificence, but on a renewed and restored Yamuna like the one that Shah Jahan and the people of 17th century India once knew. I hope in other words that we the living can supplant death with life. Here is a new article in the Boulder Weekly about my ongoing Sensing Ice exhibit that touches on my broader (but related) academic research, including some of my reflections on the relations between the humanities and the sciences. I entrusted an undergrad in journalism with some pretty complex ideas. I think it turned out reasonably well.

I'll add just a couple of things that didn't quite get conveyed in this piece: 1) I think that the humanities should engage deeply with the sciences (in sharp contrast to much of so-called "postmodern" thinking), but nevertheless that they should not serve or model themselves off of the sciences (I have in mind here particularly analytic philosophy, which I believe has fallen into this trap). My own approach is dual and seeks partly to bring humanities out into the field, both alongside scientists and as its own unique endeavor. This is contextualized especially by the disturbing, unnecessary, and unfortunate stark decline (in enrollment, academic job prospects [tenured humanities positions], and cultural relevance) of the humanities. 2) A significant portion of this project was undertaken as a solo human-powered expedition that was one of--if not the--hardest journeys I've ever completed. It follows a series of expeditions I have undertaken (especially in Alaska, but also globally) that seek to shine a light on environmental issues in far-flung places--what I call "expeditions with purpose." This is something I hope to continue to develop. 3) My closing statement about the feeling of standing on a remote ridge was nested within a comment (the context of which was dropped) about the long-standing presence of Inuit and other indigenous people's throughout the Arctic. I am well aware of this and in fact have been drawn to the Arctic in part because of this. I believe that wilderness protection (to which I allude at the end, though not by that name) is primarily about staving off industrial incursions and exploitation and need not be contrary to the recognition of landscapes as partly cultural and as traditional homeland. In fact, a persistent theme of my academic inquiry is directed at this complicated intersection between nature and culture. Relatedly, when I use the term "exploration", I mean it in a personal sense (discovery for myself, or at a unique moment in time [everywhere after all--even crowded cities--endlessly await rediscovery--by new eyes and in new moments]), not in an absolute sense. With few exceptions (notably Antarctica), almost everywhere on earth has had other people around for a long time (though to varying degrees - high mountain tops or places like the interior of the Greenland Ice Sheet for instance were far less visited and populated, and undoubtedly at least some pockets of the earth were never visited or populated). I was recently "spotlighted" by the University of Colorado's Center for Humanities and Arts. Find it here.

In the winter of 2017-2018, I had the wonderful opportunity to spend a month in India (in better days) with the primary purpose of attending an international conference on World Heritage Sites and nature conservation. On the way back, my flight from Delhi to Denver routed through Heathrow in London. As it happens, this route traverses extraordinarily far north over Greenland, Baffin Island and Hudson Bay in Canada. My trip to balmy India thus turned remarkably into a scenic flight over the Arctic in the dead of winter.

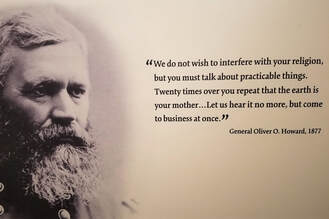

By an accident of timing, the entire flight was in daylight as we raced ahead of the sun, while the weather was remarkably clear. Northern Ireland and Scotland peeked out of the fog, eastern Greenland was sealed in a layer of cloud, but before long I caught glimpses of Greenland’s ice sheet and massive maritime glaciers and black cliffs. The sea ice of Hudson Bay seemed to stretch on forever. At times, the ice appeared in great solid peninsulas, and at other times it had an odd texture like a frog’s skin or paint chips tightly scattered across the sea. I could only imagine how large each of those chips really was. This wasn’t mere daylight, but the perpetual light of a winter sunset—the white expanse reflected a soft orange glow. For thousands of miles. I stared out the window in awe of this immense frozen landscape. As it happened, one of the inflight movie options was a Red Bull documentary entitled Into Twin Galaxies about a small group of explorers who kite-skied across Greenland’s ice cap to access a remote whitewater river. I took turns watching it and gawking out the window. I knew I had to go. Not just for adventure, but because I was convinced of Greenland’s central importance in the world’s future. And that it was an exceptionally beautiful place that I just had to see for myself. This three-and-a-half-year-old vision is finally coming to fruition this summer. I am due to arrive in Greenland in two weeks with the purpose of working on two amazing projects. The first is a NEST (Nature, Environment, Science, and Technology) Studio for the Arts project with the primary purpose of bridging art and science through writing and photography (https://www.facebook.com/nestcuboulder/). Based on my time in Greenland and a previous trip to Nepal, I will put together an exhibit with the assistance of two PhD students specializing in glacial science (and possibly a helpful friend or two) that will hopefully go on display this winter in Boulder. The second project is a Pulitzer Center environmental journalism grant focused on the relationship between the U.S. and Greenland in the context of climate change, with an additional focus on the science taking place on Greenland’s glaciers and ice sheets. I have a nice website for this and just wrote my first post: https://pulitzercenter.org/projects/legacy-us-relations-greenland-era-climate-change. Please check it out. I hope also to do a little adventuring on glaciers, rivers, or seas. I plan to post intermittent updates and photos on Facebook, Instagram (https://www.instagram.com/Chrisdunnonplanetearth/), and here on my blog. General Oliver O. Howard to Chief Joseph (Hinmatoowyalahtq'it) and Nez Perce (Nimiipuu) in Montana (1877) "The earth is the mother of all people, and all people should have equal rights upon it. You might as well expect all rivers to run backward as that any man who was born a free man should be contented penned up and denied liberty to go where he pleases" --Chief Joseph (Hinmatoowyalahtq'it) in Washington D.C. in 1879

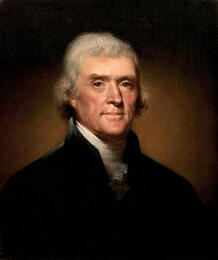

"State a moral case to a ploughman and a professor. The former will decide it as well, and often better than the latter, because he has not been led astray by artificial rules."

--Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) "neither science nor philosophy is needed to know what one has to do in order to be honest and good, and indeed wise and virtuous."; "judgment...can be confused and deflected from the right direction by a lot of inappropriate and irrelevant considerations." --Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) "Socrates could never get tenure in a philosophy department today. That Socrates could never get tenure today is an indictment of the system--a reductio ad absurdum--not an indictment of Socrates"

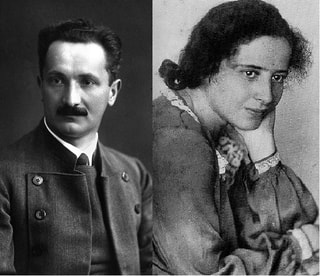

"my hearers always imagine that I myself possess the wisdom which I find wanting in others: but the truth is...the wisdom of men is little or nothing" --Socrates (-470 -- -399) "Heidegger has always been the essential philosopher."

—Michael Foucault (1926-1984) "The most thought-provoking thing about this thought-provoking time is that we’re still not thinking." —Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) "Thinking is a lonely business." —Heidegger to Hannah Arendt in Hannah Arendt (2012) This New York Times opinion piece, When Philosophy Lost its Way, is a fantastic take on the often-dismal state of contemporary philosophy.

"There was a brief window when philosophy could have replaced religion as the glue of society; but the moment passed. People stopped listening as philosophers focused on debates among themselves." "Having adopted the same structural form as the sciences, it's no wonder philosophy fell prey to physics envy and feelings of inadequacy. Philosophy adopted the scientific modus operandi of knowledge production, but failed to match the sciences in terms of making progress in describing the world. Much has been made of this inability of philosophy to match the cognitive success of the sciences. But what has passed unnoticed is philosophy's all-too-successful aping of the institutional form of the sciences. We, too, produce research articles. We, too, are judged by the same coin of the realm: peer-reviewed products. We, too, develop sub-specializations far from the comprehension of the person on the street. In all of these ways we are so very 'scientific.'" I streamed my first ever Facebook Live event last night--a Fireside Chat on Earth Day 2020 focused on the topic: "Which is preferable as an activity (which would you give up if you had to): Fire or Television (including streaming)?"

Watch it here "Homo erectus appeared, roughly 1.8 million years ago. Until recently, the earliest human hearths were dated to about 250,000 B.C.; last year [2012], however, the discovery of charred bone and primitive stone tools in a cave in South Africa tentatively pushed the time back to roughly one million years ago." (source) "The overpowering rise of machinery pains and frightens me; it is rolling along like a thunderstorm, slowly, slowly; but it has taken its direction, it will come and strike."

--Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) as Susanne in Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre “Possibly, in our intuitive perceptions, which may be truer than our science and less impeded by words than our philosophies, we realize the indivisibility of the earth—its soil, mountains, rivers, forests, climate, plants, and animals, and respect it collectively not only as a useful servant but as a living being, vastly less alive than ourselves in degree, but vastly greater than ourselves in time and space...” --Aldo Leopold (1887-1948)

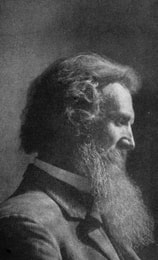

“Why does this strange man go into the wet woods and up the mountain on stormy nights? Why does he walk along on barren peaks or on dangerous mountains?”

--Toyatte (Chilkat) “It has always seemed to me that while trying to speak to traders and those seeking gold mines that it was like speaking to a person across a broad stream that was running over fast stones and making so loud a noise that scarce a single word could be heard. But now, for the first time, the Indian and the white man are on the same side of the river.” --Chilkat chief Dan-na-wuk |

Chris Dunn, PhD

Researcher, writer, explorer*, photographer, thinker. Wrestling with nature, culture, technology. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

*When I use the term "exploration", I mean it in a personal sense (discovery for myself, or at a unique moment in time [everywhere after all--even crowded cities--endlessly await rediscovery--by new eyes and in new moments]), not in an absolute sense. With few exceptions (notably Antarctica), almost everywhere on earth has had other people around for a long time (though to varying degrees - high mountain tops or places like the interior of the Greenland Ice Sheet for instance were far less visited and populated, and undoubtedly at least some pockets of the earth were never visited or populated). It is an enlightening experience though when on an isolated ridge in what feels like the middle of nowhere to wonder if anyone has set foot there but never knowing for sure. What is significant is that the landscape itself is left in such a condition that it isn't evident. Some places ought to be kept that way.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed